Ceclazepide (TR2-A)

- Ceclazepide is a novel gastrin blocker and a prodrug, which delivers its active component, TR2, efficiently into the bloodstream.

- The patent application for ceclazepide was recently approved in Europe and the USA. Approval is pending in other countries1.

- Chronic toxicology studies were ‘clean’.

- In pre-clinical studies, ceclazepide was not quite as potent as netazepide. However, preliminary studies in healthy subjects suggest that ceclazepide and netazepide are of similar potency (Figure 1). Also, ceclazepide is more selective and soluble, and easier to formulate than netazepide.

Figure 1. TR2, the active moiety of ceclazepide, and netazepide active pharmaceutical ingredients cause similar dose-dependent block of pentagastrin-induced stomach acid production in two groups of healthy subjects (unpublished).

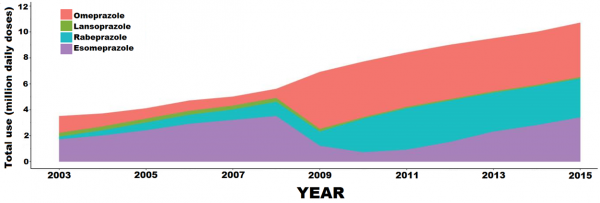

- Like netazepide, ceclazepide blocks gastric acid production. The market for acid-related conditions is substantially greater than that for g-NETs. For example, at least 5% of people in the western world take a PPI, usually for symptoms caused by backflow of acid (reflux) from the stomach into the oesophagus (gullet). There are 114 million prescriptions each year in the USA at a cost of $14 billion. And PPI use is increasing2 (Figure 2). Although PPIs are well tolerated, their long-term use is associated with adverse effects, such as increased risk of bone fractures3,4 and cancer of the gullet in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus5–9. Also, two recent huge surveys of many thousands of patients in Hong Kong10 and in Sweden11 have shown that long-term PPI use is associated with a three-fold increase in gastric cancer. Although association does not imply causality, evidence is growing that the villain is the secondary hypergastrinaemia12.

Figure 2. Increase in PPI use in Iceland during 2003-2015

- The American Gastroenterological Society recommends that PPIs should be prescribed at the lowest dose on a short-term basis13. However, many patients have persistent acid-related symptoms that require long-term therapy. A gastrin blocker like any other acid suppressant, increases gastrin production, but the increase is ‘harmless’ because the gastrin receptors are blocked. Addition of a gastrin blocker to a PPI would also renders ‘harmless’ the PPI-induced increase in gastrin production14,15. Therefore, ceclazepide, with or without a PPI, offers advantages over a PPI alone, for long-term treatment of persistent acid-related symptoms.

- Vonoprazan, a novel potassium competitive acid blocker for treatment of acid-related conditions, also causes hypergastrinaemia16,17, which a gastrin blocker should render ‘harmless’.

- Gastrin induces proliferation in Barrett’s oesophagus, and PPI-induced hypergastrinaemia is associated with advanced oesophageal cancer in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus5–9. A trial of the effect of netazepide on biomarkers in Barrett’s patients is in progress18.

- In patients with cancer of the pancreas that had not metastasised, a gastrin blocker called gastrozole, prolonged survival, albeit not significantly, compared with 5-FU and placebo. Gastrozole had to be infused continuously into a vein, so it wasn’t developed further19 (Figure 3).

- Compared with placebo, a gastrin blocker called proglumide significantly increased survival of patients who had undergone surgery for gastric cancer, but because proglumide is a weak and unselective gastrin blocker, it wasn’t developed further20 (Table 1).

- Netazepide prevented stomach ulcers induced by an NSAID (aspirin-like treatment) in an animal model21.

Potential clinical indications for ceclazepide

- acid reflux, either alone or combined with a PPI

- Barrett’s oesophagus, which is mainly caused by acid reflux

- H. pylori infection, in combination with antibiotics. H. pylori, a germ that causes peptic ulcers and stomach cancer and is found in the stomach of half the world’s population; the inflammatory response to H. pylori is gastrin driven

- non-ulcer dyspepsia

- prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers

- pancreatic cancer

- stomach cancer

Figure 3. Survival curves in patients treated with the gastrin blocker gastrozole* (n=29), 5-FU (n=20) or placebo (n=5) for pancreatic cancer that had not yet metastasised

- 301 patients were randomised to proglumide thrice daily or no additional treatment for 5 years after surgical removal of part of their stomach for cancer of the cardia³ (Figure 4), which is common in China.

- Proglumide prolonged survival significantly (p=0.04) and was safe and well tolerated.

Table 1. Randomised, controlled trial of proglumide* in patients in China after surgery for cancer of the cardia of the stomach

* Proglumide is a weak and non-selective gastrin blocker and has never been marketed.

Figure 4. Cancer of the stomach, especially involving the cardia, is common in China

References

- Boyce MJ, Thomsen L, Gilbert DA, Wood D: Benzodiazepine derivatives as CCK2/gastrin receptor antagonists. Patent WO 2016/020698. 11 February 2016.

- Hálfdánarson Ó, Pottegård A, Björnsson E, Lund S, Ogmundsdottir, Steingrímsson E, Ogmundsdottir H, Zoega H. Proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a nationwide drug-utilization study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2018; 11:

- Fraser LA, Leslie WD, Targownik LE, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, CaMos Research Group. The effect of proton pump inhibitors on fracture risk: report from the Canadian Multicenter Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 2013; 24: 1161–1168.

- Aasarød K, Ramezanzadehkoldeh M, Shabestari M, Mosti M, Stunes A, Reseland J, Beisvag V, Eriksen E, Sandvik A, Erben R, Schüler C, Boyce M, Skallerud B, Syversen U, Fossmark R. Skeletal effects of a gastrin receptor antagonist in H+/K+ATPase beta subunit KO mice. J Endocrinol 2016; 230: 251–262.

- Haigh CR, Attwood SE, Thompson DG, Jankowski JA, Kirton CM, Pritchard DM, Varro A, Dimaline R. Gastrin induces proliferation in Barrett’s metaplasia through activation of the CCK2 receptor. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 615–625.

- Wang JS, Varro A, Lightdale CJ, Lertkowit N, Slack KN, Fingerhood ML, Tsai WY, Wang TC, Abrams JA. Elevated serum gastrin is associated with a history of advanced neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1039–1045.

- Green DA, Mlynarczyk CM, Vaccaro BJ, Capiak KM, Quante M, Lightdale CJ, Abrams JA. Correlation between serum gastrin and cellular proliferation in Barrett’s esophagus. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2011; 4: 89.

- Quante M, Abrams J, Lee Y, Wang T. Barrett esophagus: What a mouse model can teach us about human disease. Cell Cycle 2012; 11: 4328–4338.

- Lee Y, Urbanska A, Hayakawa Y, Wang H, Au A, Luna A, Chang W, Jin G, Bhagat G, Abrams J, Friedman R, Varro A, Wang K, Boyce M, Rustgi A, Sepulveda A, Quante M, Wang TC: Gastrin stimulates a CCK2 receptor-expressing cardia progenitor cell and promotes progression of Barrett’s-like esophagus. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 203–214.

- Cheung K, Chan E, Wong A, Chen L, Wong I, Leung W. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut 2018; 67: 28–35.

- Brusselaers N, Wahlin K, Engstrand L, Lagergren J. Maintenance therapy with proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e017739

- Waldum HL, Fossmark R. Proton pump inhibitors and gastric cancer: a long expected side effect finally reported also in man. Gut 2018; 67: 199–200.

- 11 https://www.gastro.org/press/aga-releases-best-practice-advice-on-long-term-ppi-use

- Boyce M, Dowen S, Turnbull G, Berg F, Zhao CM, Chen D, Black J. Effect of netazepide, a gastrin/CCK2 receptor antagonist, on gastric acid secretion and rabeprazole-induced hypergastrinaemia: a double-blind trial in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 79: 744–755.

- Boyce M, van den Berg D, Mitchell T, Darwin K, Warrington S. Randomised trial of the effect of a gastrin/CCK2 receptor antagonist on esomeprazole-induced hypergastrinaemia: evidence against rebound hyperacidity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 73: 129–139.

- Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Hori T, Kudou K, Nishimura A, Hiramatsu N, UMegaki E, Iwakiri K. Randomised clinical trial: vonoprazan, a novel potassium compettive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the healing of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Thar 2016; 43: 240–251.

- Graham D, Dore M. Update on the use of vonoprazan: a competitive acid blocker. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 462–466.

- Abrams J. https://clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01298999

- Black JW. Reflections on some pilot trials of gastrin receptor blockade in pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 360–364.

- Chen YP, Yang JS, Liu DT, Yang WP. Long-term effects of proglumide on resection of cardiac adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 2549–2551.

- Webb D-L, Rudholm-Feldreich T, Gillberg L, Halim MA, Theodorsson E, Sanger GJ, Campbell CA, Boyce M, Näslund E, Hellström PM: The type 2 CCK/gastrin receptor antagonist YF476 acutely prevents NSAID-induced gastric ulceration while increasing iNOS expression. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2013; 386: 41–49.