Gastrin in health

- Gastrin is a hormone secreted by G cells in the stomach lining. At physiological concentrations, gastrin controls gastric acid production, and repairs and maintains the stomach lining1.

- When we eat food, G cells release gastrin into the bloodstream. Gastrin stimulates gastrin receptors (also called CCK2 receptors, CCK2 R) on enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in the stomach lining to release histamine, which in turn stimulates histamine H2-receptors (H2R) on adjacent parietal cells (acid-producing cells) to secrete acid into the stomach via the proton pump in the parietal cells. As acid rises, and food passes out of the stomach, it switches on D cells in the stomach lining to release another hormone, somatostatin, which enters the bloodstream and switches off gastrin production by the G cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Normal stomach

Hypergastrinaemia

Anything that reduces gastric acid production (hypoacidity) results in persistently increased blood levels of gastrin (hypergastrinaemia), which leads to: irregular gene expression in cells of the stomach lining; increased growth of those cells and their potential to metastasise (spread); and reduced apoptosis (natural cell death)2. All of those effects increase the risk of malignancy.

The main causes of hypoacidity and hypergastrinaemia are:

- Autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), a condition in which patients make antibodies against their parietal cells3. Hypergastrinaemia causes growth of ECL cells and, in some patients, formation of multiple gastric neuroendocrine tumours (g-NETs), formerly known as gastric carcinoids. Recent surveys from referral centres in Europe and the USA report metastasis rates of 8%4 and 19%5 at presentation. CAG patents also have a seven-fold increased risk of gastric cancer, probably because of their hypergastrinaemia6.

- Inflammation of the stomach lining by infection with H. pylori bacteria. A study in an animal model has shown that hypergastrinaemia is the cause of the inflammation7. H. pylori is also the main cause of stomach ulcers and gastric cancer8.

- Medicines that suppress acid production, such as a proton pump inhibitor (PPI)9 or potassium-competitive acid inhibitor10,11 and are mainly used to treat heartburn and indigestion caused by backflow of acid (reflux) from the stomach into the oesophagus (gullet).

- Mutations of ATP412 or KCNQ1/KCNE113 genes in the proton pump, which can lead to formation of g-NETs and gastric cancer and the need for surgical removal of the stomach12, even in children.

Stomach of patients with hypoacidity and hypergastrinaemia

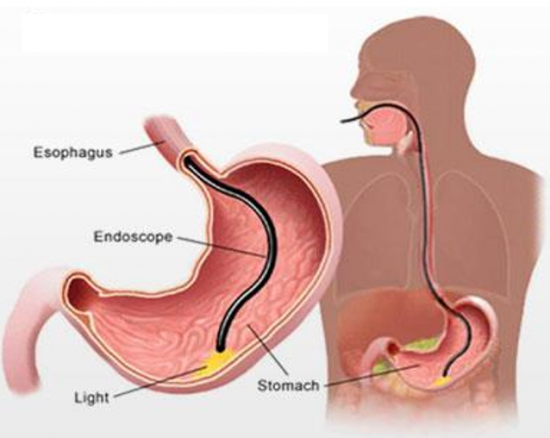

In the hypoacidic stomach of patients with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) or mutations of genes controlling acid production, somatostatin production by D cells is not switched on and gastrin production by G cells continues. Hypergastrinaemia ensues and causes ECL-cell growth and, in some patients, g-NETs (Figure 2), which can be seen at gastroscopy (Figures 3 & 4). Although PPIs also reduce acid production and cause hypergastrinaemia, there are only a few case reports of g-NETs in patients on long-term PPI therapy14,15.

Figure 2. Formation of g-NETs

Figure 3. Gastroscopy

Figure 4. Gastroscopy of CAG patient with multiple g-NETs

(pH 7 indicates that there’s no acid production)

Current recommended treatment of g-NETs16,17

- Gastroscopy once or twice every year

- Surveillance of small tumours

- Map and biopsy (snip) the tumours with the gastroscope for histology analysis (examination under the microscope).

- If there are concerns, such as excessive growth or invasion of the stomach wall by a tumour, remove the tumour with the gastroscope or remove surgically the part of the stomach that makes gastrin (antrectomy) or the whole stomach (gastrectomy). There’s no licensed medicine for treating g-NETs, so there’s a big unmet need. Because g-NETs are gastrin driven, the ideal medical treatment is a gastrin/CCK2 receptor antagonist (‘gastrin blocker’). No gastrin blocker has ever been marketed.

- However, g-NETs are usually multiple so it’s difficult to remove all of them, and they can regrow. Furthermore, antrectomy isn’t always successful, and antrectomy and gastrectomy carry the risk of morbidity and mortality.